| English Page |

A life dedicated to the rights of Indigenous People |

|

|

| 06 September 2011 | ||||||||

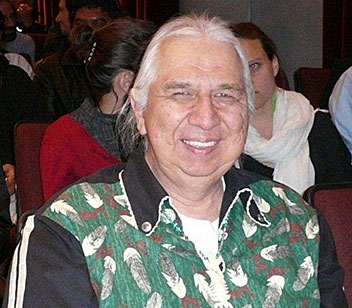

Interviewing Kenneth Deer

“One of the greatest problems with modern society is its non-existant link with the Earth, the environment, plants and all creatures” Can you give us a brief description of the work of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peopless? The purpose of the Mechanism is to provide advice to the Human Rights Council about the rights of Indigenous Peopless, so its job is to perform studies and research at the request of the Human Rights Council. Right now, they have completed a study on the Indigenous Peopless’ right to education and we’re still looking at how this will impact Indigenous Peoples. They are currently completing another study on Indigenous Peopless’ right to participation and decision-making in all affairs affecting them. The Mechanism is defining the rights that are in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by flashing through all of them and taking some of those rights, whicht are articulated therein, and telling the Human Rights Council how these rights should be applied and how they should work. It’s a very important role and we've got a lot of work to do. There are so many references to different kinds of rights in the Declaration and the Mechanism must further articulate these rights, so there'll be for many years to work on that. What is the relation between this Expert Mechanism and the Permanent Forum on indigenous issues? The Permanent Forum is in New York and it’s a body of 16 human rights experts and there that has a broader mandate to look into a wide spectrum of issues that affects Indigenous Peoples, such as environment, education, health, all social issues, land and territory. Its job is to compile all the information they can on these issues and to produce a report.

It's different from the Expert Mechanism because the Permanent Forum is not really doing specific studies on specific rights. Its area is to advise the United Nations systems and agencies on all issues that affect Indigenous Peopless; therefore, the two bodies have a different mandate. Furthermore, the Forum is a bigger body that is actually rather large; and there’s a lot of participation in their meetings - you get about 2.400 people at their session. Following the adoption of the Declaration, what is really changing for Indigenous Peoples? I think that what's changing is the fact that Indigenous Peoples have not had a tool, a legal tool to help them assert their rights. Before the Declaration, they didn't have that. They didn't have a document that could guide them to articulate what those rights are, you know. Now, with the Declaration printed in many languages, Indigenous Peoples have an understanding of what their rights are and it helps them when they have to deal with states, multinationals, local communities in their area, and regional governments. So it helps them clarify their thinking, clarify the debate and, I think, it's been helping a lot of people have a better understanding of what their rights are. Not only Indigenous Peoples, but non-Indigenous Peoples have also been educated on those rights and it's also very helpful. The Declaration is not a binding instrument. It's not international law. It's a declaration; however, the rights that are articulated in there are binding in other instruments, such the right to self-determination, which is mentioned in the Declaration under Article 3, which says that Indigenous Peoples are peoples; hence, have a right to self-determination. That article is also in the Covenants on civic and political rights, and social and cultural rights in the form of Article 1, so those are binding instruments. Therefore, the Declaration points to those binding international laws and what should apply. That’s what makes the Declaration so important and so strong. The governments are obligated to follow those laws which they were reluctant to recognize in the past. Do you think that the Expert Mechanism can help the application of the Declaration by the governments? Yes. It gives advice on issues and does not provide conclusions or recommendations. It advises the Human Rights Council, which is made up of 54 States, I believe, that all States are to take that advice and publish it; and present it by saying: “this is how the right to education for Indigenous Peoples should be applied or the right of participation, this is how the experts are saying this right should be used”, you know. So it plays an important role in defining States application of the Declaration. You have been involved in this works for many years. Are you satisfied about the steps that the United Nations have taken for Indigenous Peoples? Well, satisfied wouldn’t be the right word I would use, I would say that it’s improving, it’s better. When I started first coming here twenty-five years ago in 1987 there was only one group, the Working Group on Indigenous Populations and there was no Declaration. When I started to come I think we had 12 or 13 articles in the draft Declaration.

So many things have changed since the Declaration. Now it’s 46 articles and we have the Expert Mechanism, the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and many Indigenous, I guess there are avenues in other UN agencies like WIPO and the IGU, and other conventions on diversity. All of these avenues now are mentioned so Indigenous Peoples are getting involved in a broader range, a broader field, in the United Nations system. And slowly, the United Nations are also hiring Indigenous Peoples. We have a few Indigenous Peoples who currently work on indigenous issues. There are Indigenous Peoples and it’s really important to have that. There's a lot of change that has taken place in 25 years. It's slow, it takes a long time, and I would say the United Nations moves at the speed of a glacier; but it does move and things do happen. We have a long way to go yet because we haven't reached the end, and this is just another step, and we must use those steps to create more steps. And that's what we're going to do. So, am I satisfied? I'm satisfied that we’ve made game and I won't be satisfied until we get everything that we think we need to survive. Which steps are next? The next step is the actual implementation of the Declaration. The rights that are enshrined in the Declaration now need to be applied and there’s still resistance to that from States and the private sector, you know. We still have to find ways to educate States and ordinary people on the Declaration and we have to find ways to apply those rights that are articulated in there. It’s gonna be a long road and it doesn’t happen overnight; but I think in 20 years from now I’ll be looking back at the Declaration saying “Wow, what a fortunate thing that we were able to get the Declaration because of the changes made”. That’ll be slow. We’re waiting now for court cases in certain states that’ll be using the Declaration to help judgment in a positive way to defend the rights of Indigenous Peoples; and that’ll be significant. There's a jury school that builds up over the years with the Declaration, so it will be a very significant event. So, that's what we're looking at. We're looking at Indigenous Peoples asserting the rights that are articulated in the Declaration and where we go from there. So, that's the next step. Can you tell us something on your personal experience throughout all these years with Indigenous Peopless? Well, I think that when I started coming here there was such a diversity of Indigenous Peoples from all over the world. We knew that there were Indigenous Peoples in North, Central and South America. We knew that there were Indigenous Peoples in Australia, New Zealand; but it was news to find out that there were Indigenous Peopless in Scandinavia, in Africa and Asia. We learned about them, so that taught me a lot. There is also so much solidarity between Indigenous Peoples because we all had the same struggle, we've all been disempowered, we've all been dispossessed and we’re all fighting for that recognition and the right to exercise self-determination. It was a learning process to me and even defining things. I knew I was indigenous. I knew I was a Mohawk. I knew who I was, but I didn’t understand totally understand what rights we have; and I didn‘t understand the UN system or the international system, so I had to learn.

We all had to learn how to be diplomatic. We had to learn to be more sophisticated in how we articulate our positions and so it’s been a tremendous learning process; but I learned a lot, not only from Indigenous Peoples, but also from non-Indigenous Peoples who were here to support and help. A lot of sympathy, you know. Lots of resistance from some of the absolutely silly positions that states declare, such as “we don’t have Indigenous Peoples in our country” or “Indigenous Peoples are less than all other peoples”, you know. We still get that and we still feel that racism. It’s still here and we’re still fighting that. It’s so engrained; and I call it “institutional racism”. There’s so much institutional racism against Indigenous Peopless, not only in our home countries but internationally and we’re still fighting that. My experience show that it continues to be there; and, although we're chipping away and reducing it, we still have a lot to do and, well, I feel optimistic. If it’s anything I learned here it’s that as long as we're minorities we have to continue the struggle, and if you stop struggling, that's when we do disappear, and that's what States want us to do. They would love Indigenous Peoples to disappear into assimulation so they could say: “we’ve gotten rid of the indigenous problem ‘cause now they're gone”. And we can’t let that happen, I won’t let that happen, I won't let our people disappear and we're gonna teach our children and our children's children not to disappear and how to use the Declaration, use the UN to make sure we survive the future generations. I think that there is the same spirituality in common among all differences... |

-->

-->